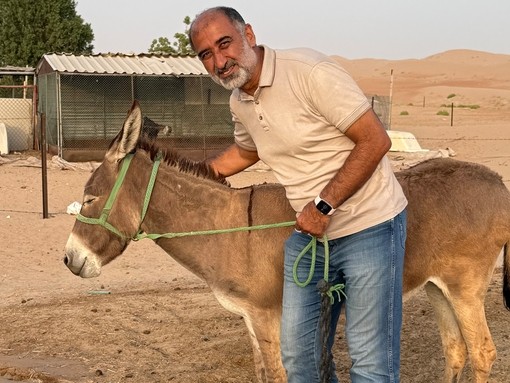

An interview with Dr Abdul Raziq Kakar

How did your childhood embed your love of donkeys?

If I tell you my background, then you will understand why I have a deep connection with livestock. I am from an agrarian, semi-pastoralist family in Northeast Balochistan, Pakistan. We had sheep, goats, camels, cows and sometimes one or two donkeys. As soon as I opened my eyes, I saw these animals around me.

In the village at that time, there was not much machinery - not even a tractor - so we were ploughing with the oxen. We used donkeys for fetching water and bringing the fodder for the cattle. The donkey was, in my opinion, the most obedient, hardworking animal, but always received less respect and care. The words people use to call someone stupid relate to the donkey, but the donkey is the opposite - I knew this from when I was a child.

I was a child shepherd. We had our own flock of sheep. People usually think that we manage grazing flocks with shepherd dogs. But they forget that the donkey is more than a dog, they are super intelligent. When you go out as a shepherd, you just take a little bit of luggage, bread, your flock and your donkey. The donkey will never need your help, and they even protect the flock from wolves and other wild animals.

Last year, on World Donkey Day, I connected with African shepherds on Twitter and they are replacing security people or dogs with donkeys, because they do a better job protecting the property and livestock, and confronting wild animals!

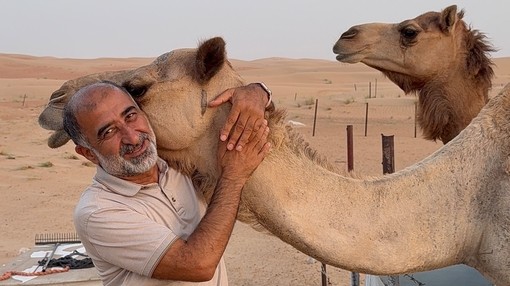

You are also a camelogist. What does that involve?

Many people have stopped consuming dairy products because they see cows suffering. We have our own model, where we try our best to operate ethically. We provide large spaces where they can walk and exercise. We do not separate the calf from the mama until they are eight months old. We keep their housing very clean, airy and dry.

What are the similarities between camels and donkeys?

When I studied my PhD, I explored which animal was the best in drought conditions. We are facing the challenge of climate change, so we are looking for adaptation and resilience, especially because Pakistan is not industrially advanced.

In the area I studied, there had been drought for 10 years. I asked the local people about their livestock. The answer to my first question, ‘In hot arid conditions, which animal can still provide us with milk?’ was the camel. But when it came to the resilience of the animal to survive, to sustain, the donkey was on top!

If I could have focused on donkeys in my research I would have, but I couldn’t find a supervisor who would support a donkey-focused project. Still now, if anyone wants to do research, project or work in any part of the world on donkeys, I would support them voluntarily. We need to look through the lens of nature at the donkey.

How did your work develop after your PhD?

After my PhD, I wrote about the donkey. Then I started to do talks everywhere. When I was talking about the camel, I was talking about the donkey too. I found like-minded people, like donkey expert Dr Peta Jones who teaches about donkey management in South Africa. She revitalised my knowledge, connection and passion with the donkey. I was delivering my presentations online at that time.

Meanwhile, there was breaking news in the donkey world. The very sad news is that in Africa the illegal trade of donkey skins is rife. In many cases, thieves stole donkeys and killed them to remove and sell the skin. Even in Pakistan, many donkey skins were illegally exported. Nobody knew where the meat of the donkey went. It is likely it was illegally mixed somewhere into the food system, and cooked and eaten by the people.

I am actually not against using donkeys as livestock. If you have a farm, you produce more, but in an ethical way. But please don’t steal the donkey from the rural people. I have met many people where their only income source is the one donkey. They have a cart to transport goods and other things, and the donkey earns the food, the kids’ school fees, everything. So if someone kills a donkey to take the skin, they are causing the collapse of a family.

Can you tell me more about the role of donkeys in tackling environmental challenges too?

I went to Frankfurt, Germany, in 2007. They had realised that there was no new germination of pine trees. They went to scientists, but they didn’t have an answer. In the end, the older people told them that there used to be donkeys in the area. The donkeys had eaten the plants and spread the seeds. When we looked at another project in Europe using livestock in ecosystem management, they had introduced the donkey. In the areas grazed by the donkey, we could see hundreds of new pine plants.

In Abu Dhabi, UAE, we had two Arta plants close to my office. It’s a very special desert plant that grows up to three metres high. I browsed camels on them when there were seeds, now we have more than 2,000 plants in the same area. You could hire labour, technology, use fossil fuels and produce maybe three tons of carbon dioxide when camels and the donkeys are the real solution. I’ve consulted on a project in Saudi Arabia to introduce camels and donkeys into the construction process, where they will be able to bring as much biomass to the desert as you could produce on river deltas.

How did World Donkey Day come into existence?

The so-called ‘developing countries’ are industrialised. They always look for one thing; to increase their exports. I was always saying, “No, please open your eyes - this is the donkey of the people, it’s not a farmed animal. This is entirely different.” We have to redefine livestock. I was always in a fight with the policymakers in Pakistan - I was a one-man army. I have one laptop, and I went to many universities and other places. I told the people, “Please talk about the donkey”. They were ashamed to do it.

Then I made a small group called SEVS - Society of Animal, Veterinary and Environmental Scientists. I gave it an attractive name to emphasise that we are scientists! I found more support, especially from the donkey breeders from Balochistan and from the Ministry of Agriculture. We ran a very good programme in 2010 in the capital of Balochistan, Quetta.

After discussing it with many people, in 2010 I said, “We will celebrate World Donkey Day!” We had to do our part - and people would either listen or not. Our role was just to do our best. Peta Jones was also a really strong voice in this - she was the one who highlighted the first of May is World Labour Day and, as the donkey is a very important labour animal, World Donkey Day should be in the next week.

In 2009, I started World Camel Day and people started talking about the camel. When I started World Donkey Day in 2010, I thought no-one would be interested, but believe me it exploded. We found out for the first time that there are feral donkeys in Australia. We heard about donkeys in Africa, China, Ethiopia and Mexico. The next year there were celebrations in America, Australia and in Pakistan. In Pakistan it was even featured on the TV. I said, “Oh my gosh, I should have spent all my 30 years on the donkey, maybe I would be the president of some country!”

What would you love to see for camels and donkeys?

I would love to see the camel, as well as the donkey, not defined by humans. These animals are not just for food, work, riding, racing and recreation. They are created by nature to enrich nature, revitalise nature, sustain nature, spread seeds, to provide diverse microbiomes and enrich the soil.

What is the future of this work for you?

My main work will be giving talks - at universities, and everywhere! To spread the word to respect the donkey and their importance. While I do the talks, there are other people working on practical things. For example, they are making good equipment for use with donkeys in farming.

I will go back to my village and talk about using donkeys for multi-dimensional purposes. You can use donkeys on small farms as a ploughing animal, a working animal. You can use them to pull rickshaws. We can reintroduce the donkey back into society because it is an important and incredible, biological machine.

When I was doing my PhD work, there was this one mountain in the Suleiman mountainous region. On the top of this mountain is a tribe called the Mirkhani, who are nomadic. They have a unique species, a special line of the Shingharri donkey, and breed them. The price of one breeding female donkey is equal to three local lactating cows with their calves. This is unheard of in most other places. They are very famous for their donkeys because they love and respect their animals. I want this viewpoint taken everywhere.

Find out more about Dr Raziq and his work

Visit his websiteShare this page

Tags

- Blog